The morning I had been waiting for, the Ka’iwi Channel Relay, a 40 mile outrigger canoe race, crossing from Molokai to Oahu, had arrived. This relay race is paddled in a one person outrigger canoe where you switch out  with your partner every 30-45 minutes, requiring an escort boat. The Ka’iwi channel is notorious for its reputation of being one of the toughest ocean channel crossings in the world because of its strong winds, currents and large swells. Situated in the middle of the Pacific ocean, with exposure to thousands of miles of ocean to the north and south, it also has significant sea floor features that adds to its dynamic seas. A submerged volcano called Penguin Bank lies to the west of Molokai and within the Kaiwi Channel. It is a broad shelf of 10 miles wide and 20 miles long with relatively shallow water of depths from 12-180 feet. The channel’s maximum depth is 2,202 feet. Strong tidal currents are typical at the edges of the shelf where there are changes in depth, sometimes generating confused sea states and adding another element of challenge for navigating a single outrigger canoe or any vessel.

with your partner every 30-45 minutes, requiring an escort boat. The Ka’iwi channel is notorious for its reputation of being one of the toughest ocean channel crossings in the world because of its strong winds, currents and large swells. Situated in the middle of the Pacific ocean, with exposure to thousands of miles of ocean to the north and south, it also has significant sea floor features that adds to its dynamic seas. A submerged volcano called Penguin Bank lies to the west of Molokai and within the Kaiwi Channel. It is a broad shelf of 10 miles wide and 20 miles long with relatively shallow water of depths from 12-180 feet. The channel’s maximum depth is 2,202 feet. Strong tidal currents are typical at the edges of the shelf where there are changes in depth, sometimes generating confused sea states and adding another element of challenge for navigating a single outrigger canoe or any vessel.

As soon as James, my relay buddy, and I, got out of bed on race morning, we headed out to study the beach launch closely on the west side of Molokai. We, Team Ocean Love, were relieved to see that the surf had subsided making getting off the beach possible and not frightening for our race start. The night before, we watched the north swell pound the beach, the forecast predicted the 8-10 ft. NW swell to drop overnight to 4-7 ft.  The sound of powerful surf thundered all night waking me regularly as I tried to sleep.

The sound of powerful surf thundered all night waking me regularly as I tried to sleep.

After the pule, the prayer ritual before races, everyone headed to the beach to launch canoes. There were sizable surf , 4-5 ft coming from the north. With patience, I waited for the lull in the surf and sprinted off the beach through the surf zone. Timing was everything to avoid capsizing my canoe. Our next challenge was swimming gear out through the beach break to our escort boat. I noted that other paddlers used fins for the swim out which we did not have. James swam the gear out for us. It took a lot of work and energy to swim with our luggage. I was grateful for his swimming ability and comfort in the surf zone, being an avid surfer.

The minutes leading up to race starts often feel a bit chaotic for me. This was no exception. After having launched through the surf zone, I was paddling among a fleet of 54 escort boats who were either looking for their paddlers or retrieving swimmers outside the surf zone. To add to the action, race official boats zipped around while racers in their single canoes were darting around to warm up. Our plan was for James to start the race. As  rookies to this relay race, we hadn’t thought about the transition needed from swimming gear out and time to get ready for the start. As I surveyed the scene, I realized I should be the one starting the race. What felt like moments later, James and our escort boat driver pull up. James still has his heart set to start the race. I just go with it. As soon as James’ mounts the canoe, he immediately capsizes, appearing a bit rattled from the swim out. He leaps back on again and capsizes a second time before sprinting to the start line. I climb onboard the escort boat to join our captain.

rookies to this relay race, we hadn’t thought about the transition needed from swimming gear out and time to get ready for the start. As I surveyed the scene, I realized I should be the one starting the race. What felt like moments later, James and our escort boat driver pull up. James still has his heart set to start the race. I just go with it. As soon as James’ mounts the canoe, he immediately capsizes, appearing a bit rattled from the swim out. He leaps back on again and capsizes a second time before sprinting to the start line. I climb onboard the escort boat to join our captain.

Moments later, a loud blast from the race horn signals the race start. Our pack of canoe paddlers sprint off. We start our journey across this sacred ocean channel, just specks in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, so exposed. The visibility was less than ideal at the start. From Molokai, on a clear day, you can barely see the silhouette of Koko Head and Makapu Point on Oahu, but this morning, these land features were not in sight from our vantage point. Until we could see Oahu, we relied on our captain and his GPS to guide us to stay on a direct line from east to west, thirty miles of open and exposed ocean channel.

Moments later, a loud blast from the race horn signals the race start. Our pack of canoe paddlers sprint off. We start our journey across this sacred ocean channel, just specks in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, so exposed. The visibility was less than ideal at the start. From Molokai, on a clear day, you can barely see the silhouette of Koko Head and Makapu Point on Oahu, but this morning, these land features were not in sight from our vantage point. Until we could see Oahu, we relied on our captain and his GPS to guide us to stay on a direct line from east to west, thirty miles of open and exposed ocean channel.

After 30 minutes, we find James among the pack of 54 paddlers that has already become very spread out. We spot him with his bright lime green neon shirt, the pink striped canoe and his curly white hair. At 40 minutes, we give him a five minute warning, the captain lines up the escort boat ahead of the canoe while I jump into the water to change out with James. This becomes our routine switching every 45 minutes until the finish line on Oahu.

Flying fish greet me during my first piece as I happily paddled along feeling the rise and fall of the ocean swell. As I settled in, finding my rhythm, I looked for smaller wind waves to catch and to build speed in order to connect with larger and faster moving swells. As soon as my speed increased and the back of the canoe would rise up, I would point the nose of the canoe down the steep face of the large swell. I’d take 3 quick strokes and catch a downhill ride, increasing my speed from 5-6 mph to 10-12 mph, a sensation of dancing along with the ocean. Smiling, I would look for the next ride. I was most challenged when converging waves would just push me around like a pinball, slowing me down and requiring me to re-group. One time, I had thought I could get a push forward from a quartering wind wave on the crest of a large swell and the energy was more powerful than I expected. The energy of the wind wave surprised me by bumping me off of my canoe and into the water. I jumped back onto the canoe giggling and humbled by its power. Ocean swell are like fluid hills that also require grinding uphill. Every forty-five minute piece went by so fast when I was on the canoe. So fun!

swell. As I settled in, finding my rhythm, I looked for smaller wind waves to catch and to build speed in order to connect with larger and faster moving swells. As soon as my speed increased and the back of the canoe would rise up, I would point the nose of the canoe down the steep face of the large swell. I’d take 3 quick strokes and catch a downhill ride, increasing my speed from 5-6 mph to 10-12 mph, a sensation of dancing along with the ocean. Smiling, I would look for the next ride. I was most challenged when converging waves would just push me around like a pinball, slowing me down and requiring me to re-group. One time, I had thought I could get a push forward from a quartering wind wave on the crest of a large swell and the energy was more powerful than I expected. The energy of the wind wave surprised me by bumping me off of my canoe and into the water. I jumped back onto the canoe giggling and humbled by its power. Ocean swell are like fluid hills that also require grinding uphill. Every forty-five minute piece went by so fast when I was on the canoe. So fun!

As NOAA weather predicted, the conditions in the channel were mixed with combined seas, North swell 5-7 feet and South swell 3-4 feet, a rising tide current running northerly, and 15-25 NE wind. In the Kai’wi channel, rarely does wind and swell line up to create good conditions for consistent waves to surf. The sea state changed as we crossed. Early in the day, we had big rollers with wind waves and white caps. Later, as the current and wind increased, the swell steepened and smaller waves would form ontop of the crest of the swell. Gusts of winds would come and go. Photos and videos could never fully capture the true scale of the ocean state and the steep faces we surfed down. So much energy. The energy exchange of various elements converging. As a paddler, I was constantly reading the water to find a way to tap into that energy. Once we were close to Hawaii Kai, the waves got smaller, much like the conditions we have in San Francisco Bay. I felt at home, skipping along toward the finish.

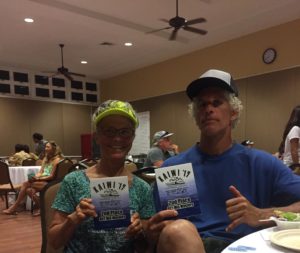

Six hours later, we arrive tired, humbled and happy at Kaimana beach, the finish line, completing our shared endeavor and epic odyssey. For the second time, I experienced this channel crossing in a single canoe. I felt good about our race. James was a solid waterman, relay partner and friend. I came away learning so much and aware that I have so much more to learn about paddling big ocean conditions skillfully, relaxed and efficiently. I was honored to be among elite paddlers who are masters and make paddling these ocean conditions look effortless. The Kai’wi channel lived up to its reputation for being grueling, demanding and long, confirming that it exists in a league of its own. Exposure. No hiding. Facing conditions that arise. I love what the channel demanded from me- focus, being present and connection. Aloha. Team Ocean Love.